The Turnbull Government’s naval shipbuilding enterprise is estimated to be worth almost $90 billion and the primes are scrambling to build their local supply chains as they either begin work on announced contracts or finalise their bidding for others.

This is good news for small and medium enterprises around the country which are already part of the global supply chains of companies like ASC, Lürssen and Naval Group - or the Sea 5000 contenders, BAE Systems, Fincantieri and Navantia.

But what of the SMEs who have perhaps traditionally supported the mining or automotive industries and have not worked with the shipbuilding primes or in the Defence space before? Some smaller companies who have some experience in this domain might be disadvantaged because their process or skills are not up to date, so how can these companies bid for a slice of the action?

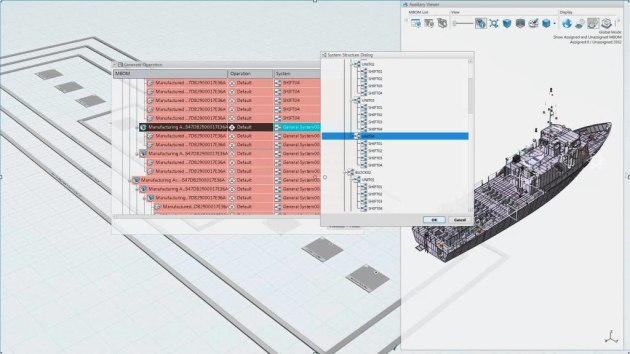

In partnership with the South Australian Government, 3D design software, 3D digital mock-up and product life-cycle management (PLM) solutions company Dassault Systèmes has created a regional training centre, known as the Virtual Shipyard, to ensure that SA’s supply chain is on par with the rest of the world.

Under the partnership the Virtual Shipyard is co-funded by the SA Government and the Federal Government’s Advanced Manufacturing Growth Centre (AMGC), together with Dassault Systèmes.

Narayan Sreenivasan, geo leader, Business Transformation AP South for Dassault Systèmes, explains that the company had been working with ASC on the Collins Submarine program. As part of an assessment into industry capability during the digital transformation journey, gaps were discovered in the skills and competencies within the local SA supply chain.

This, coupled with the SA Government’s desire to build digital capabilities within the state’s supply chain, was the catalyst for the Virtual Shipyard.

“Digital alone will not bring them where they need to be. It needs to be digital transformation, plus some very specialised processes and practices around Defence shipbuilding that need to be brought together and imparted to a set of local suppliers - and that could also expand into other States,” Sreenivasan says. “The shipyard does not have the capacity to build an entire ship, a large part of the ship is made up of the components and sub-systems built outside the yard and that means you need to virtually expand the shipyard into its supply chain.”

The Virtual Shipyard program began with an initial batch of 16 SMEs a little over a year ago and is running courses in two tranches of eight SMEs each. These will run for six months, after which further development can be undertaken at the company’s own facilities using courseware and software provided.

“A large number of Australian suppliers are playing in the Tier Three and below space. We want to build them into a Tier Two and above supplier, not just a commodities supplier,” Sreenivasan says.

“Some of the shipbuilders themselves are keen to participate also, because they stand to benefit from an elevated supply chain.”

Sreenivasan adds that the Virtual Shipyard program also has academia on board, with participation so far from the University of Adelaide, University of South Australia and TAFE SA. “They are acting as SMEs. They have placed some of their academics in the program to learn alongside the SMEs and we are bringing in consultants from academia and industry to help them formulate what they’ve learned and that will be used to develop course content that can align to Bachelor and Masters Programs in Defence,” he says. “We can then build up a pool of resources at the exit of university that can be directly absorbed by the SMEs.”